Max Kreijn

tulip fever

painting

2RC Rome - 2001

Curated by Arianna of Genova

The interior day. Summer vapors permeate the walls of a house. There is no one in the room. Neither a voice nor a noise. Just a table set against the wall, covered with a checkered tablecloth, with a vase of tulips in full bloom. In the sparkling silver of the containers, the obsessive grid pattern of the tablecloth is reflected and the shadows of tulips, threadlike ghosts, appear and disappear in the background. The eye approaches and in that insistent "blow up", the sharpness falls apart, the light clouds, the colors gush between the lines.

These theatrical notes have never been written but belong by right to an imaginary canvas by Max Kreijn: Tulip fever (2001), the painting that mimics a "still life" is a complex stage machine where the ordinary life of objects / subjects becomes an affective construction, a metaphysical composition. The Dutch artist who proposes a dramaturgy of light and splits reality into a series of “wings” of very pure fiction. Everything is immobile, rarefied, on the balance of abstraction. On the canvas - an oil, which stands out on display among the other watercolors - a meridian light has congealed. It seems to penetrate through the window, but it hits the vase and flowers at its discretion, according to a fantastic, almost cartoon-like projection.

Then, suddenly, something moves. A human figure, a naked, sculptural body, entered that room and animates its atmosphere. It is shielded by a black band, as if it were acting inside a movie film. The fever given off by tulips (the title of the work refers to a book that tells of the eccentricity of the economy of a country, Holland, which was based on flowers in the seventeenth century) attacks the body, making it palatable and sensual.

Kreijn knows that by contaminating photography (the portrait) and painting (the "glimpse") magic can take place: the overthrow of the world. Now, in fact, the smooth and velvety skin of man is marble like Michelangelo's David, while the vase of tulips loses its two-dimensional fiction, acquires carnality and becomes a habitat. No longer painted but a walkable space, a passable place. Just play the game and enjoy the gift of Hyper-vision ", modifying our perceptive activity, just like you do in the theater, spectators of a double of reality that veers towards the dream and then, with rapid flashbacks, reverses the march and returns to the starting point. The unreality - Baudrillard writes in The symbolic exchange and death - is no longer that of the dream or the ghost of a beyond or this side, it is that hallucinating resemblance of the real to itself ”. Thus in the mirroring of things within one's own reflection, in multiplying the fragments, in the seduction that underlies the seriality of objects, we arrive at counterfeiting, at the hemorrhage of Reality. The new product is the simulacrum.

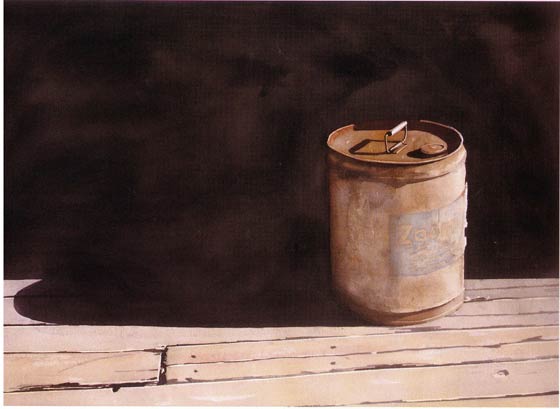

Max Kreijn loves to travel in search of summer and sunlight. That is, he loves to give voice to the invisible by capturing an object at the moment of its true birth: just hit by a golden ray, when it feeds on the right light, the unique and special one, which resists a moment and then goes away, throwing away a jar , a shutter, a door or a window in its leaden anonymity. If, on the other hand, one is able to grasp the aura, the perfection of a summer dust, the heat that exudes from a Roman wall, the imperceptible wind that hisses between the curtains of Bologna or the half-light that creeps between the slits of the shutters Palermo, then those apparently bare domestic interiors or those semi-closed doors of the cities acquire a different thickness, are dressed in mystery, are transformed into theatrical characters, unaware actors of a grandiose luminous epic.

The representation from life - Max Kreijn travels and takes thousands of photographs that are epiphanies of the banal, details and angles of images that have been lived and yet never "looked at" before - soaks and becomes liquid again in the artificial light invented by watercolor. The play of transparencies, the shadow holes, the black smoke that cloud the pupil are all ingredients that the artist needs to create a sort of theater of absence, an optical and psychological suspension.

Beyond that backdrop that interrupts the flow of life, fleetingly encrusted with light, there is the eye of Vermeer, the surreal melancholy of Hopper, the light-hearted irony of Pop, the skilful deception of advertising. Above all, together with the heat of the summer season, there is the “cool” universe of digital media that Max Kreijn's watercolor, in contrast with its “landscape” and academic use, awakens and relaunches.