2RC Stamperia d'arte

New York

Text by Walter Rossi from "La vita è segno"

In Italy, in the 70s, the political and economic climate was difficult. The usual flow of American artists who came on vacation every year to enjoy the beautiful country had completely stopped. In this way, we lost some wonderful job opportunities that we had been able to seize for years.

Since 74 we have been looking for solutions to prepare a base for a printing house in New York that would thus be a physical presence. I was sure that in that city, knowing about theirs, they would have accepted us favorably.

Arnaldo Pomodoro gave me a wonderful opportunity. He had been invited by several universities to take courses during the year, as is customary in America. For him at that time it was necessary to have a studio in New York. He found, through some artist friends, a large loft in Soho, beautiful but too big for him.

He asked me if we wanted to take it together and my answer, without even having ever seen him, knowing Arnaldo, was enthusiastic.

Before defining the agreement with Coop. Broome Street, owner of the building, Arnaldo was officially commissioned to teach for a few years no longer in New York but in San Francisco. With great regret he asked me if he could give up his share. I accepted willingly, absolutely not wanting to miss the opportunity to join that cooperative of artists where there was a huge waiting list.

I signed the agreements directly from Italy. I only knew that it was a palace from 1848, the “Silk Building”, born as a factory where silk was worked. I had been assigned the fourth floor, but there was no problem there to support the weight of the machines we would have to install.

I think the day I first saw the Silk Building I was breathless.

A splendid palace which, I learned only later, was a national monument. Extremely severe in its 14 floors, under a copper roof oxidized by time which contained and compensated, with its discreet intrusiveness, the excessive architectural repetitiveness of the façade.

It was different from all the lofts I had seen over the years in New York. Normally, in lofts, the only positive thing is large spaces, often sacrificing brightness with small and rare windows, certainly not conceived as light sockets or for looking out.

Our studio had a large number of windows, very bright; the smallest was two by two meters, and from there you could see Broadway traffic passing beneath you. What was even more surprising was the orientation: north-east, the best for an artist studio.

The thing that surprised me was that the aesthetic quality of the exterior was not repeated inside. Instead, there were anonymous walls with frames dripping with overlapping paint and rickety wooden floors. The services part was comparable to a public toilet. Instead, the exciting thing were the spaces, indeed the space, a huge parallelepiped full of light that generously lent itself to every possible realization.

Before doing any project we began to attend the studio at all hours of the day; we slept there for a couple of nights, a bit camped but satisfied. We became physically aware of the violent fascination that this city, always alive 24 hours a day, had on us.

The palace itself, in that incessant factory of noises, participated in the great metropolitan concert, unusual to our ears, which came from steam systems for heating.

The most excruciating noise was that of the sirens. The fire trucks, which started at full speed from Broome Street and headed for every part of the city as they crossed Broadway, just below us, slowed down, blasting that piercing sound, making us imagine catastrophic situations.

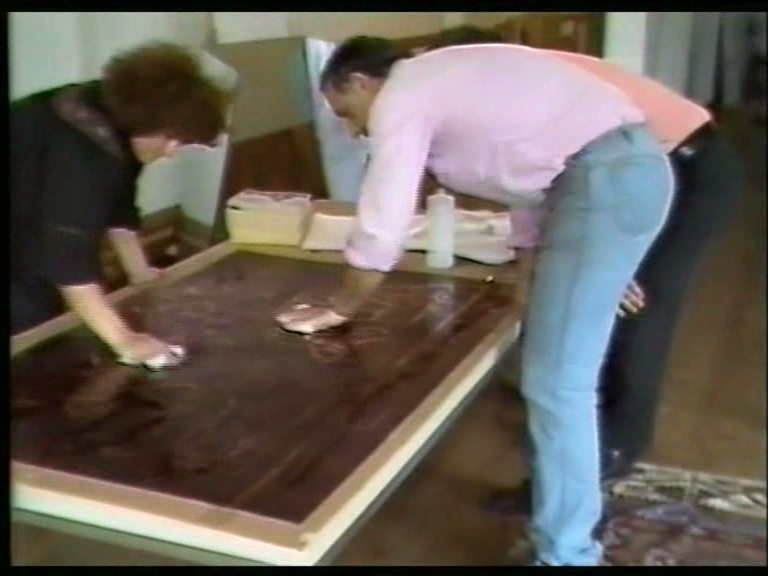

We began the work with a first company, then with various others that alternated for months, not to finish the works as we had them, with love, thought and drawn in detail. To be able to finish, I hired a Caribbean sailor from Granada, whom I had met in Turkey, embarked on a very old Greek boat, owned by elderly Italians.

Good Anthony enjoyed the utmost confidence, as he was capable of everything from carpentry, to plumbing, to electricity. He did everything with great skill and responsibility.

With Anthony's help we finally entered the New York studio, where he remained as my assistant.

The most worrying thing was the installation of the large press which, designed and built in Italy, as light as possible, still reached three tons.

We found a company specialized in transport of this type, which thought of organizing the bureaucratic and administrative things necessary in that area where traffic does not stop and conditions every operation on the island.

Traffic was stopped on Broadway and Broome at 9.00 am and diverted for two hours into parallel streets by firefighters who set up barriers and appropriate markings. Immediately after, the vehicle arrived with a huge crane installed. I never imagined they would push a three-ton press with a crane out of one of the windows on the fourth floor.

The press entered and, as if by magic, when I went up, I found it positioned as expected. It seemed to be part of that space, born as a workplace more than a hundred years earlier.

The whole building participated with interest in the operation and in the end we celebrated.

Looking from the outside, a few days later, I realized how much energy had been needed to be able to carry out that imaginative undertaking.

Operation started from a Roman studio at the Baths of Caracalla, now it was located in the center of Manhattan. It had fallen like a meteorite, almost by accident, and was accepted, in no uncertain terms, as a logical consequence.

For a long time, during the night, opening my eyes, I wondered where I was, and every time I was surprised to be in that place of our own; I looked at Eleonora who was sleeping peacefully next to me, protected by those walls, in that immense heterogeneous agglomeration so complex and different for us.

For the first time in many years of coming to New York, right and only there, we unconsciously realized that we were in a friendly space, in that aggressive city.

Pierre Alechinsky wanted to be the first artist to work in New York. He had recently found a studio in Up Town, and this was a wonderful coincidence that we took advantage of.

Pierre thought of a very New York triptych: “Soleil noir”. Three large intense and severe images, born from plates engraved to the point of pain, like wanting to dig with your nails in the basalt, basalt on which this city is founded. Then all that remains is to look for the sun, going towards it, but squinting until you see the black.

Working with Pierre, who clearly knew which path was to be followed, was the best way to start the studio on a positive path. The only thing to check was the efficiency of the press that was waiting for nothing else. With its maximum range of one and a half meters of light for four meters in length, it certainly did not fear a Pierre slab: one meter by one meter! He printed it, already at the first stroke, in an admirable way.