Henry Moore's Studio

Versilian copierative

Pietra Santa

Text by Walter Rossi from La vita è segno

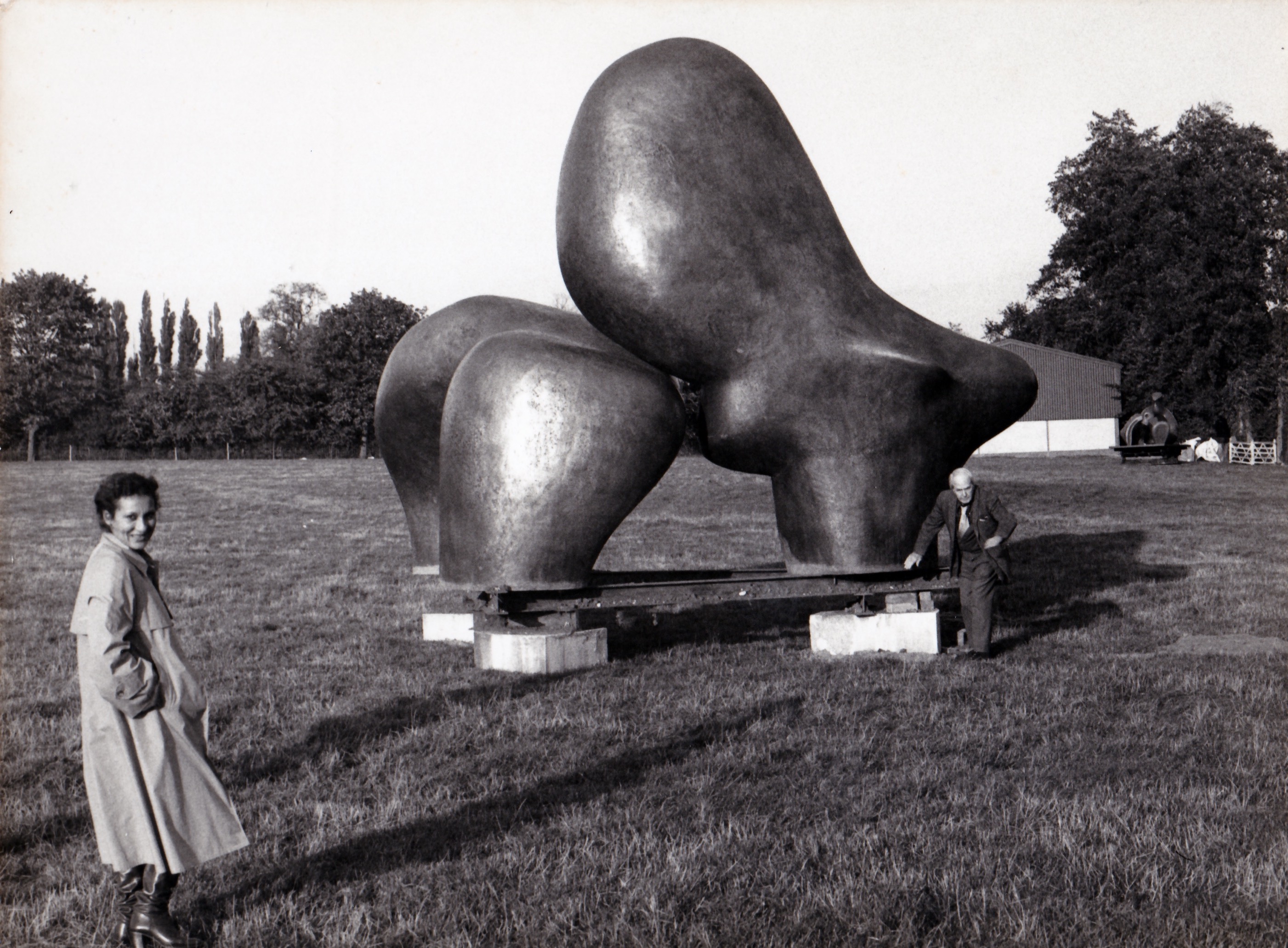

Finally, during the summer, I had the idea of organizing a studio in Pietrasanta, near his summer home. Here, for thirty years, Moore used to spend about three months with the "first" purpose of working marble in one of the oldest and most serious workshops in Versilia.

So I set up our studio at the “Cooperativa Versiliese”, which also specializes in quarries and marble processing. The owner friend was enthusiastic, only at the idea, of being able to meet and host, through us, the great sculptor.

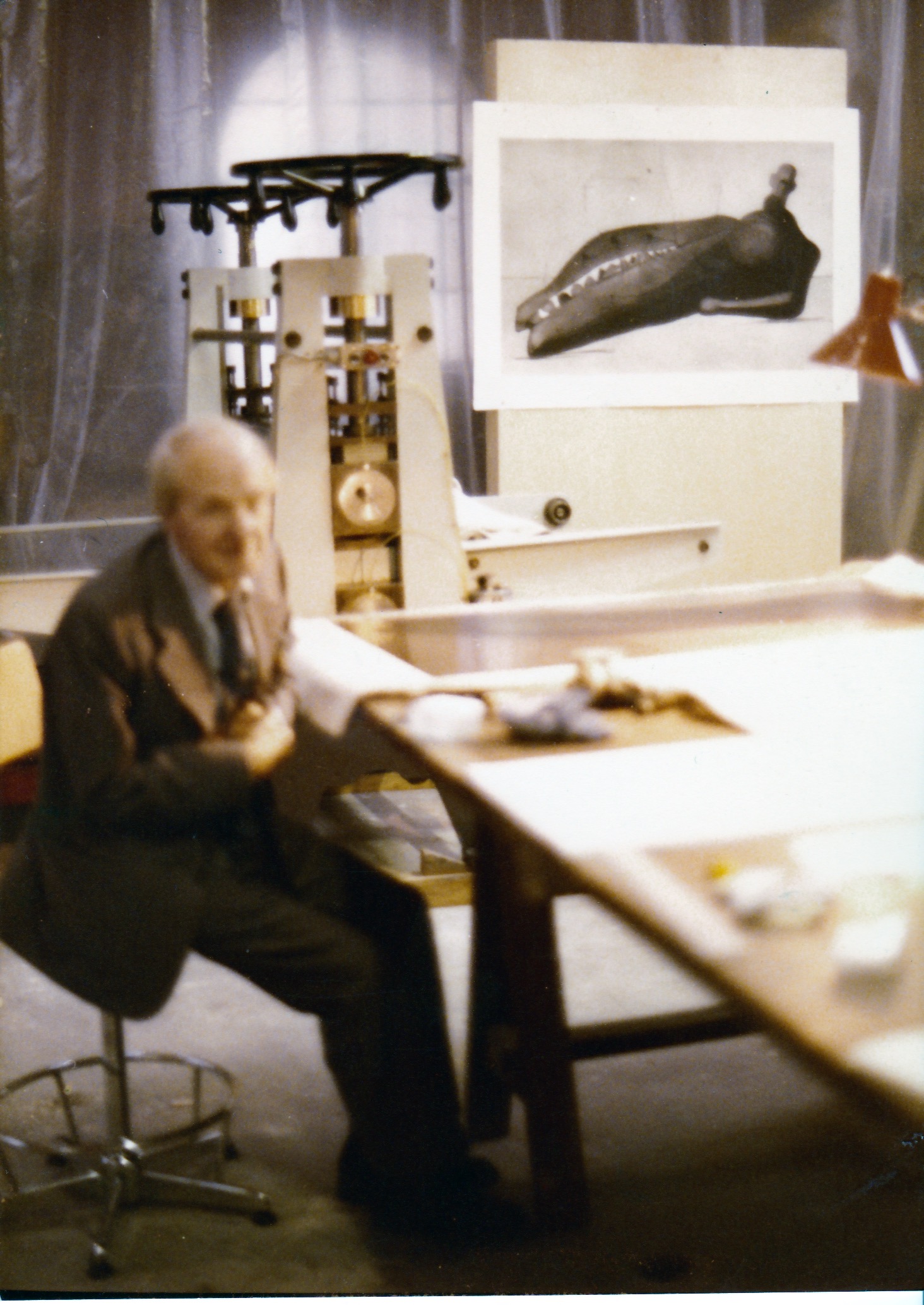

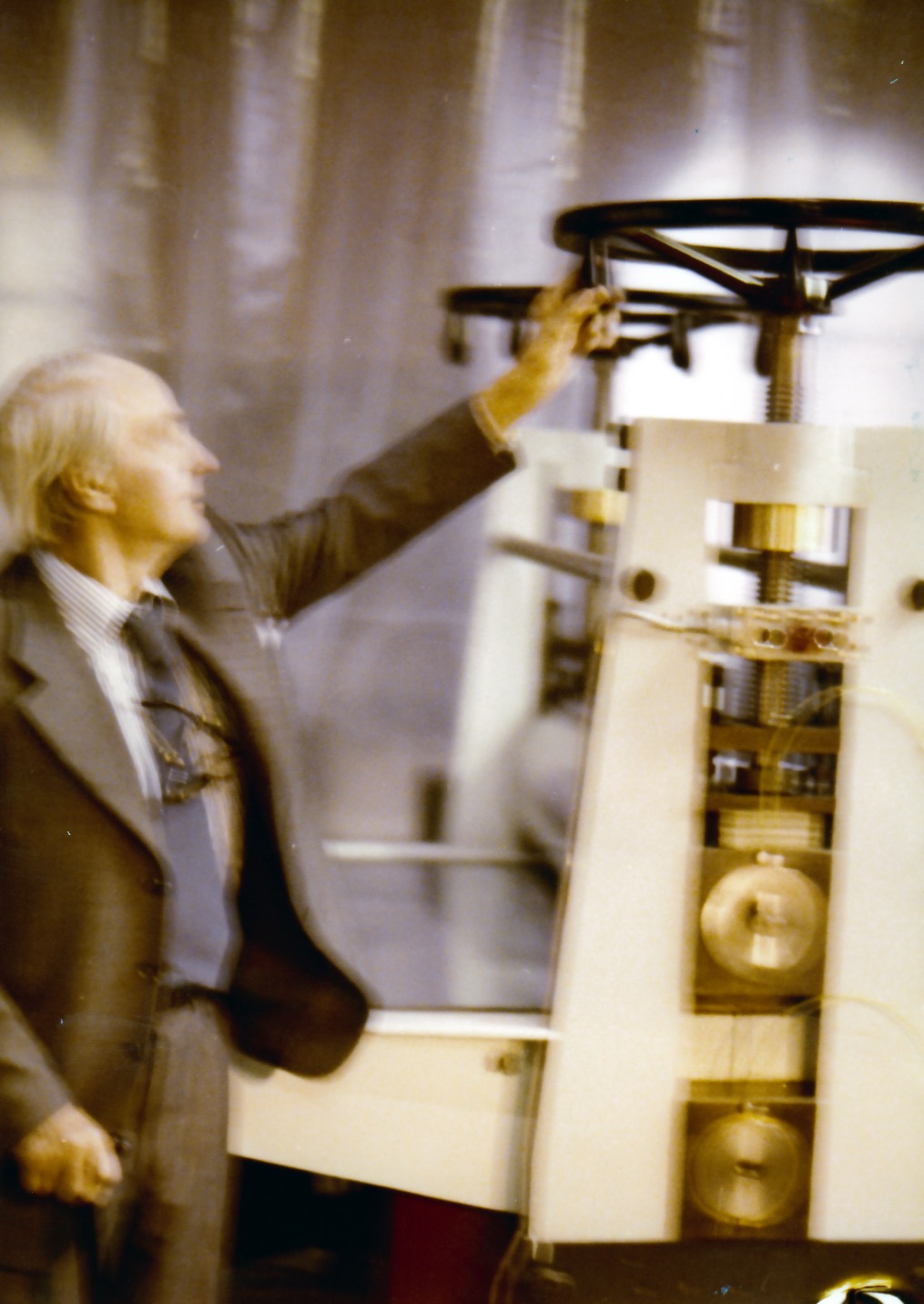

A large, very simple space was placed at our disposal, in which we mounted the press we had built at the same time as the one we had shipped to America. We had designed it specifically to be easily assembled in artist studios, and we completed the installation with all the necessary equipment for printing.

The work experience we had with the English artists Victor Pasmore and Graham Sutherland helped us a lot because Henry Moore, while frequenting Italy continuously since the war, had not been touched in the least in his way of being and watched everything that happened. around, every time with amazement, because events occurred that went out of his schemes.

Henry Moore had, in the past, worked a lot in etching with splendid small engravings that followed, in some way, his sketches, probably using them to engrave in his memory and to recover, from them, sensations useful for reading his sculptures. He was looking for a setting that, on paper, he found more easily.

He had never entered into the merits of the press as a concrete medium to rely on and to feel that the time he devoted to the surface of the copper would return to him with all the strength he normally knew he was getting from stone or bronze.

This man, more than eighty years old, applied himself with incredible enthusiasm and meticulousness, to the point that if we initially thought of doing a simple experimentation, we were instead involved in a complex series of plates that grew in that space, at the beyond our imaginations.

He immediately understood the quality of the aquatint and defined it, in front of his first print: a black with its shadow. We were amazed because, with so many artists who had experimented with this technique, no one had ever described it with such precision.

Henry Moore had noticed that, based on the light and changing the point of view, the black changed strongly, the image acquired absolutely different depth values, almost three-dimensional macro.

To enhance this effect, I thought of bringing the artist to also use drypoint, a technique with which his intense figures could blend up to the white of the paper, absorbing the strongly plastic forms inside it, so as to give an effect of "pure light".

The effort to be able to deal with plates of that size with drypoint could worry even a young person. There was not a single moment in which Henry Moore interrupted a sign that had begun and, when he stopped, it was only to concentrate and leave, however, remaining on his schedule, from 9 to 12 in the morning and from 4 to 6 in the afternoon, with a meticulous student.