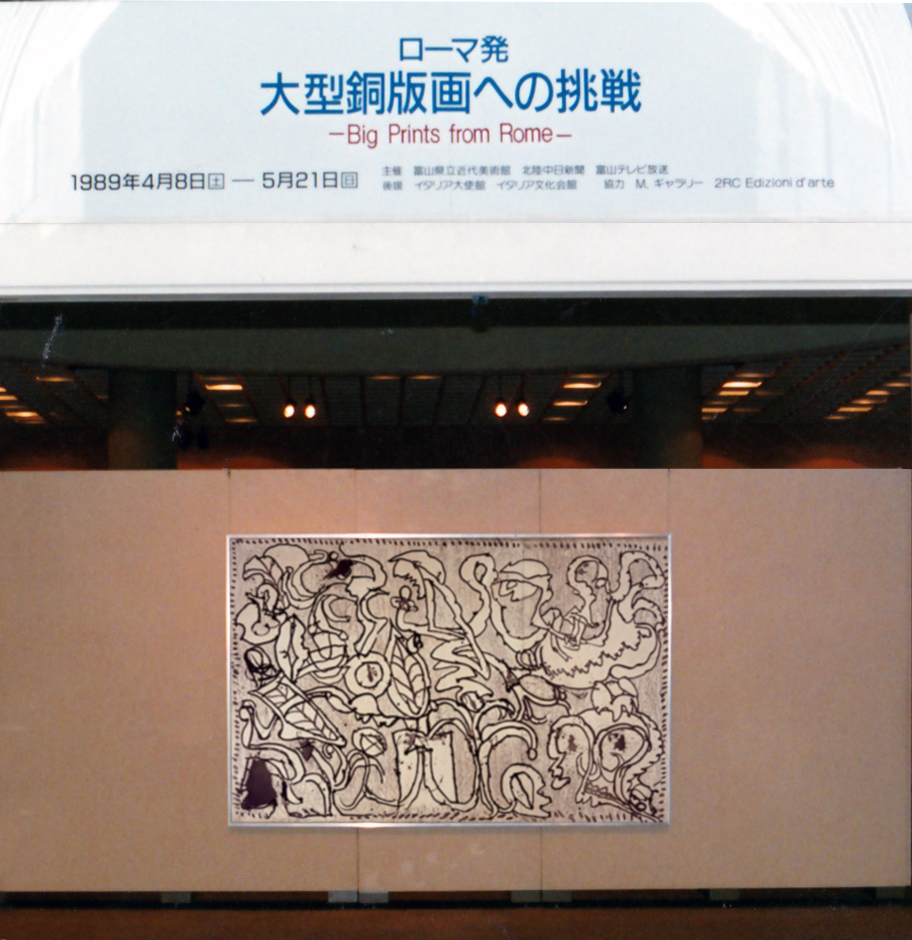

Big Prints from Rome

graphic works

Japan - 1988

Text by Andreas Freund, “Mourlot, master printer of lithography”,Art News, marzo 1973

From its beginnings to the beginning of the fifteenth century in Europe, printing has manifested itself as an international phenomenon. The generally portable size of the prints and their multiple character made them ideal vehicles for the export of art and culture. While utilitarian concerns significantly influenced the character of prints in their ancient history, their particular relationship to technology and their method of production based on the separation of distinct and sequential works had a major impact on how artists and others have seen them. In the XNUMXth century, the reproductive capabilities of technically sophisticated engravings produced in large Italian workshops spread the achievements of masters such as Raphael or Michelangelo throughout Europe creating a profitable market and also providing valuable visual information that would serve the education of generations of artists. However, despite its commercial success or cultural significance, reproductive etching ultimately contributed to a negative understanding of the creative potential of print as it linked a craftsman's extraordinary manual or technical skill with an already existing masterpiece in another medium. . Without cataloging the subsequent evolution of the original print or elaborating the exceptional contributions of painters whose engagement with the technique radically influenced its formal and expressive character, a brief consideration of the historical struggle of the print to achieve its aesthetic identity and the roles covered by artists and printers seems appropriate.

A crucial distinction exists between printmaking and painting or drawing: in the latter two, the artist's touch or mark is direct and his result, more or less immediate, whereas the processes required to realize the printed image distance him from the outcome, which is also generally reversed. From the moment liquid tusche or aquatint acid solution are applied to stone or plate, the resulting image is conditioned by a series of decisions involving tools, inks and papers, but, by far the most important distinction is that the realization of the image usually requires the participation of a skilled printer. While his involvement may vary depending on the artist's ability to assimilate techniques, it is clear that the making of prints is a collabor¬ative activity which challenges the conception of total artistic control.

Since the mid-nineteenth century the most important contributions to printmaking as an independent art form have been made by "outsiders", or the most part painters with little or no technical preparation whose inexperience, paradoxically, may have prompted them to ignore conventional procedure in an effort to find expressive means that were compatible with their general artistic goals. While these artists were occasionally inspired by the examples of innovative predecessors (as witness the impact of Goya's etchings and aquatints on Delacroix, Manet, and Degas), they still relied heavily on the advice and manual assistance of printers.

The founding of the Société des Aqua/artistes in 1862 by the publisher Alfred Cadart represented an attempt to involve some of the most progressive painters in Paris in a medium which, with rare exceptions, had become increasingly illustrative, reproductive, or specialized. The participation of Whistler, Daubigny, and Manet, among others, was facilitated by the expertise of the painter-printmaker Félix Bracquemond and the printer Auguste Delatre. Although the aesthetic significance of this enterprise was recognized by Charles Baudelaire ("l' Eau-forte est a la mode", Revue Anecdotique, April 2, 1862), he hailed it primarily as a restoration of the primacy of the artist's hand in the face of encroachments by the mechanical arts, especially photography.

If Cadart's publishing venture did not fully succeed in its objective of making etching a more viable creative medium for painters, it did inspire a few to conduct prolonged investigations. From sporadic attempts prior to his contact with Cadart, Manet's printmaking activity intensified throughout the decade. Lack of serious training imbued his initial efforts with an awkwardness uncharacteristic of traditional etching, but also caused him to work on the plate with a refreshing directness of expression. While Manet's controversial canvases provided the point of departure. for the majority of his early prints these were by no means reproductions. Instead, the repeated number of states suggest the artist's awareness that it was possible to explore the formal properties of a painted image through new constructive processes.

During the last quarter of the century the creative role of the artisan took on a new significance owing to a new emphasis on the physical properties of the print. In the 70s, the promotion of la belle épreuve by the critic and print connoisseur Philippe Burty endorsed the technical finish of prints that would enhance them as more elite commodities in the art market of the period. Delâtre's amazing skills were enlisted to serve this new transformation of the print. His introduction of special inking techniques that manifestly determined the appearance of the etchings he printed provoked concern in some quarters about the artist's undue reliance on his skill and about the subordination of the image to the printer's technique. Two decades later, artistic dependence on the technical knowhow of printers entered another phase when such pioneers of color lithography as Auguste Clot provided the processes that enabled Bonnard and Vuillard to dramatically expand the decorative and chromatic parameters of prints.

In the first half of the twentieth century, printmaking was dominated by the giants of modern art. With few exceptions, the ascendance of the avant¬garde in Paris was not initially conducive to any increase in the aesthetic importance of prints, but Fernand Mourlot's campaign to persuade artists to work in lithography proved especially fruitful in the years following World War II. By the 60s, the Mourlot shop was probably the largest in the world, and its organization reflected the traditional hierarchies of labor that characterized the European apprentice system. Picasso's work there disrupted the tight discipline and respect for conventional procedures that prevailed. Reminiscing, Mourlot observed "Picasso did everything the wrong way."* He introduced materials and methods that seemed destined to fail but always worked, and in the process he pushed expert craftsmen beyond conventions to find new solutions that would satisfy his artistic needs.

Although lithography was probably the most popular medium with European painters and one that developed an international market during the post-war years, opportunities in etching were not lacking. Picasso had worked with Roger Lacourière in the 30s learning the technique of sugar-lift etching which he continued to exploit in the 50s, and the ateliers of Lacourière, Patin, and Crommelynck were also frequented by younger abstract painters such as Hartung and Soulages.

In contrast to the situation in Europe during this period, American printmaking suffered from a lack of real involvement by major artists. Earlier in the century, the painters John Sloan, John Marin, Stuart Davis, and Edward Hopper had produced outstanding etchings and lithographs and during the economic depression of the 30s, government¬sponsored workshops created new opportunities for artists to avail themselves of graphic techniques. The outbreak of the war and the subsequent immigration of distinguished European artists had a significant impact on the development of American painting, but little effect on printmaking. The relocation of Atelier 17 from Paris to New York in 1940 by its founder S. W. Hayter provided sophisticated facilities and a dynamic teacher dedicated to experimentation in color intaglio. A brilliant technician, Hayter was convinced that artists should act as their own printers since he felt that each process determined the final aesthetic statement. A few younger painters, including Motherwell, Pollock, and Nevelson, took advantage of the opportunities at Atelier 17 with varying results. However, most American painters studiously avoided intaglio, regarding it as an essentially academic and constrictive enterprise. Indeed, it appeared to flourish mainly in the art departments of colleges and universities where printmakers influenced by Hayter taught the complex techniques and perpetuated the expressionist style associated with his workshop.

In the 50s, the energy and ambition of American painting and sculpture were accorded international recognition, but the physical and emotional scale of abstract expressionism or the vast dimen¬sions of color-field painting appeared incompatible with the relatively discreet size and circumscribed techniques of contemporaneous prints.

The almost simultaneous founding of Universal Limited Art Editions and of the Tamarind Lithography Workshop in the late 50s, and the subsequent establishment of Gemini G. E. L., signalled the initial phase of an unprecedented initiative that would virtually revolutionize American printmaking. The rise of Pop and Op art in the 60s was facilitated by a contemporaneous development of technology in the service of artists and by a cultural climate which accorded mechanically produced objects a new aesthetic importance. In this period of the "Americanization and modernization" of printmaking, the services of industrial designers and engineers were enlisted in the effort to attract artists whose work was becomingly increasingly public in scale and address. American painting's and sculpture's obsession with monumental scale was satisfied by the designing and fabrication of large presses, felts and rollers, and by the development of papers and other materials capable of sustaining over-size images.

The radical size and expanded technology of American prints as distinct from their European counterparts reflected the ambition of some printers and publishers to make them as important as paintings. Implicit in this programmatic transformation was the ever more active role assumed by technical advisors. Ironically, the popular success of these prints prompted some critics and print specialists to raise questions about whether an undue emphasis on industrial processes and materials was not compromising some of the qualities traditionally associated with prints.

Since its establishment in Rome some twenty-five years ago, 2RC Editions has been committed to the discovery of ways of preserving the autonomous physical and aesthetic properties of prints while at the same time responding to the different creative exigencies of the artists who make them. Over forty painters and sculptors from Italy, France, Belgium, Spain, Switzerland, England, and the United States have worked at 2RC attesting to its profoundly European roots and to its keen sensitivity to the diversity of artistic language in a manifestly more international art world.

In the early 60s few non-Italian artists would have considered working at a Rome-based print studio despite the long, indigenous history of printmaking and the availability of papers and materials of fine quality. Yet, in a relatively few years, a steady group of foreign visitors augmented the substantial core of native artists who were exploiting the diverse media 2RC offered. In the 70s, when more and more painters were discovering etching and aquatint, the heart and soul of its graphic arsenal, the workshop's superb facilities and impressive editions began to gain the interna¬tional respect of artists and critics.

While the decision to dedicate one's life to the perfection of one's own medium is a natural ingredient of artistic ambition, the same dedication to the perfect realization of the work of others is the mark of the virtuoso. At 2RC, two virtuosos, Valter and Eleonora Rossi, direct a staff of fourteen printers. Their personal and professional partnership began thirty years ago as students at the Academy of Fine Arts. Valter Rossi's love of prints may have been nurtured by his background since he was born into a family of Milanese typographers. A desire for independence as well as the prospect of working with a number of major artists living in Rome prompted the Rossi’s to settle there in 1959. A few years later, with Eleonora's cousin, Franco Cioppi, they set up a small workshop that served as the testing ground for their initial program of engaging the best artists available in the making of prints. Convinced that prints were autonomous statements, not poor relations of painting and sculpture, they were determined to create a supportive environment that would enable these artists to work as naturally and freely as they did in other media.

Lucio Fontana and Alberto Burri were central protagonists in the development of Italian vanguard art in the two decades following the conclusion of World War II. Each was noted for the provocative character of his approach to the materials and means of painting and their decision to work with the young and essentially unknown Rossi’s presented the workshop with the first of a series of artistic challenges which would require the innovative solutions to the printing of etching and aquatint that are the hallmarks of their modus operandi. Fontana's punctured and slashed canvases and paper works were the expressions of extensive experimentation with new spatial concepts. They provided the stimulus for a portfolio of six embossed etchings which reproposed the violation of the support. To achieve the desired effect, a zinc plate was profoundly bitten; the pressure of the press against the plate created irregular fissures and holes in the paper which contrasted with the thin embossed line produced by more finely etched areas. Printed either in stark black or white, the prints oblige the viewer to contemplate the highly articulated surface in a manner analogous to Fontana's painting while still preserving etching's inherent tactility. The brut quality of these prints, imparted by this exaggeration of technique, was unlike anything being done in other European or American ateliers.

An astonishingly textured surface is present in numerous etchings and aquatints made by Burri at 2RC between 1962 and 1973. In the 50s, the artist's utilization of burlap, tar, burnt plastic or wood, and other unpainterly materials had signalled a preoccupation with metamorphosis and decay that would have far-reaching repercussions for the work of artists in Europe and America. A small book of poems by Emilio Villa, containing three prints with two gold-leaf collages, was the first of a large number of livres d'artiste published by 2RC. It contained an etching and aquatint whose heavily cracked, monochromatic surface conveys a relief¬like presence that transcends its diminutive scale. The techniques used in the printing of this page were subsequently perfected and plate size vastly increased for the series of Cretti (1973), magisterial examples of the union of process and content in printmaking. Using a spatula, the artist applied an unconventional mixture of glue and plaster to the matrix, which, when heated, produced a highly variegated, crackled surface that was treated with waterproof varnish. Working with the negative mould, unusually thick cast-bronze plates were deeply bitten over a ten-day period. Two folios of absorbant Fabriano Rosaspina paper were joined to provide a sufficiently strong support for the relief-like impression. While closely resembling his paintings, Burri's austerely colored but supremely tactile prints also constituted an inspired meditation on the medium's ability to generate imagery through process and time.

The very nature of intaglio (tagliare: to cut) may partially explain its popularity with sculptors who have adopted to explore a more pronounced dimensionality than that encountered in prints prior to the 70s. Embossed etching has been the preferred technique in a number of prints done by Gia and Arnaldo Pomodoro. The essentially monochromatic Bandiere (1965) of the former and the intensely rust or verdigris-colored Cronaca (1977) of the latter uncannily convey the formal and physical properties of their sculptural antecedents precisely because an analogous working method which permitted the introduction of special synthetic moulds was incorporated into the preparations of the plate. The versatility of embossed etching was further demonstrated in the prints of Beverly Pepper, a long-time resident of Italy who was the first American artist to work at 1977RC. Pepper cut out shapes from a steel plate and soldered them together. The deep etching underscored the sculptural process, and the judicious mixture of colored inks - black, oxidized sienna, orange and white - created a tonality which reinforced the tactility of the plate's surface. In subsequent prints, Pepper dispensed with embossing but pursued the tactility it had first proposed by working directly on Carten the same material she used for her large sculptures. Here, color assumed a critical importance as it permitted the replication of the corrosive physical and aesthetic properties of this sculptural material.

While the more apparent properties of aquatint may have been subordinated to etching when combined in some of the prints already discussed, they are manifestly present in a small group of prints done by Giulio Turcato in 1964. A remarkable range of tonal effects from transparency to opacity emanates from this extremely painterly prints which Rossi still regards as among the finest examples of their work. In the decade that followed, the enrichment of the chromatic language of aquatint was fostered by Rossi's development of huge presses with multiple speeds and by the building of a gigantic bolte au grain. It was during this period that the number of foreign visitors dramatically increased. The markedly different responses to the expanded potentials of aquatint reflected in the prints of Victor Pasmore and Pierre Alechinsky merit particular discussion.

Pasmore's long painting career has been marked by periodic reassessments of figuration and abstraction which were manifestations of his intense receptivity to his physical surroundings and also of his fundamental concern with establishing relations between the world of organic forms and that of symbols. His prints have become genuine vehicles of research as he has often used problems or images from paintings as the starting point for new investigations of their capacity to grow organically from the material at hand. Since he first began working at 2RC in 1970, the scale of his prints and the sensuousness of their coloration have increased constantly. The purchase of a house in Malta, where he lives and works for long periods, has made him especially sensitive to the evocation of light and sea. The impact of his printmaking experience also may have contributed to a new sense of order and clarity in the surfaces of his paintings. Indeed, the serene and balanced lyricism of Burning Water ( 1982), a technical and aesthetic tour de force for artist and printer which required the subtle unification of two copper plates, inspired an admiring request from a British museum director for a painting like the print.

While Pasmore's exploitation of delicate or dark gradations of tone through aquatint may be associated with a more general tendency of painters to maximize its capacity to produce a wide range of chromatic effects, the calligraphic ex-pressionism of Alechinsky's etchings and aquatints stubbornly resisted the blandishments of color. Alechinsky's long experience with intaglio, which included studies at Atelier 17 in Paris and frequent collaborations with other artists, may have instilled a conviction that the force of his emphatic black gestures might be compromised or interrupted by color and certainly the formal and expressive coherence of the monumental A l'Aveuglette (1973) more than compensates for its absence. Since his initial work at 2RC, color had assumed a more significant though still essentially compartmentalized function in Alechinsky's paintings. After an absence of ten years, he started to work with the Rossi’s and a visit to Rome in 1988 resulted in sixteen prints which miraculously integrate the impetuous etched shapes with brilliant aquatint washes that convey the spontaneity of watercolor. Alechinsky recently admitted that the perfection and elegance of Rossi's aquatint disturbed him and that he felt obliged to provoke or subvert it. Yet implicit in this seemingly adversarial view of the roles of painter and printer is the recognition of the creative privilege of each, reflected through different means but nurtured and energized by the priorities of the work-in-progress.

Although a vast amount of critical literature on contemporary prints appeared in the United States during the 70s, knowledge of 2RC's activities was mainly generated there by the work produced by a small group of American artists who had begun to frequent the workshop on an irregular basis. Among the first of these was Adolph Gottlieb, an older representative of the New York School whose work the Rossis had admired. In 1968 they persuaded him to try etching and aquatint for the first time. That same year, Louise Nevelson produced a small black aquatint with additions of etching and drypoint and a gold leaf collage. The experience prompted her to work again at 2RC in 1973 on a group of three aquatints whose brilliant replication of torn paper combined with actual silver, mylar, and newspaper fragments to create a dynamic surface that evokes both the collages that inspired the prints and the resolute frontality and mystery of her celebrated sculptures.

Sam Francis' enthusiasm for printmaking was rare among American artists of his generation. His experiences in numerous French and American workshops encouraged him to set up his - own lithography studio in California where he has lived since returning from an extended stay in Paris in the 50s. Before meeting the Rossi’s in Rome sixteen years ago he had never attempted etching and aquatint. When it became clear that his schedule would not permit him to work there, Eleonora Rossi set out for California with some plates, paper, and a small bolte au grain. After six weeks of intensive collaboration, six prints were proofed on a borrowed etching press. When Francis finally arrived in Rome to sign the editions, he produced another group of prints with a chromatic and textural range that is still exceptional. Four years later, he embarked on the first of a series of heroically scaled and more spectacularly colored works which would ultimately comprise The Five Seasons (1985). Each print employs multiple plates and involves the superimposing of interchangeable lattice-like matrices which serve as closures for a myriad of aquatint events in predominant tones of green, orange and blue. In contrast to the more calculated formality of The Five Seasons, Francis' most recent print, executed in the New York workshop the Rossi’s had set up in 1981, is perhaps the most audacious of his long career. Like its immediate predecessors the principal technique used is aquatint; etching helps to contain large watery splashes of some twenty-five colors. Broad black gestures and small streaks of colored drypoint compete with the larger areas imparting an unparalleled sense of exuberance and movement to what is surely one of the most remarkable balancing acts in recent print history.

Like Francis, Helen Frankenthaler was already a printmaker of demonstrable accomplishment when she first began working with the Rossis in 1973. The painter was initially drawn to lithography for it permitted her to work with grease crayon or tusche on stone in a manner that corresponded to her broad brush stroke and spilled and stained color. While the procedural and time constraints of etching and aquatint did not seem particularly congenial to Frankenthaler's approach, she nonetheless began working in these techniques at U.L.A.E. in 1968 and her efforts were distinguished by a new attention to shape and more discreet color. The initial prints produced in Rome already evidenced an incredible freshness of color that was the fruit of the artist's experiments with Eleonora Rossi as well as a more distinctive concern with texture that reflected the implementation of the workshop's unique version of the sugar-lift process. Yet it was not until 1986 when she worked again with the Rossis in their New York shop that what began as a promising collaboration emerged fully in the spatially evocative and technically complex Broome Street Series. Each of the six prints required either two or three plates, commencing with a fine aquatint base, while colored washes were etched on a second plate and drypoint lines were subsequently incised on that same plate or reserved for yet another. Utilizing the aquatint plate as her point of departure and reference, Frankenthaler was able to work with considerable freedom adding other techniques to enhance its color space resonance. The palpable surfaces and eminently painterly qualities of Frankenthaler's and Francis' color etchings and aquatints emphatically refute the earlier perception of the medium as being insufficiently attuned to the sensibilities and aesthetic goals of action or colorfield painters.

If a high degree of inventiveness has marked printmaking at 2RC since its beginnings, the research has always grown out of the specific working experience. Technique is never and end in itself; it must always work for the image. In some respect, the traditional image of printers in the service of artists still prevails though the level of human and creative exchange is immeasurably warmer. According to Rossi, the artist is rarely knowledgeable about the options available and therefore the printer must develop an intuitive sense of how to direct him to those materials and techniques that will best translate his original concept. What evolves is a mutually didactic and almost symbiotic experience in which the ensuing bond of confidence enhances the prospect for further growth and exchange.

The prints of sculptors Nancy Graves and George Segal reflect different aspects of the importance of this didactic interaction. Predictably Graves' printmaking career had begun with a series of lithographs in 1972, followed by some hand¬colored intaglio prints about five years later. As artist-in-residence at the American Academy in Rome, she encountered the Rossi’s and began working on several plates in 1979. Her first black and white etching was followed by color prints combining these techniques with drypoint, which, in Rossi's opinion, allowed an additional measure of spontaneity commensurate with her work in sculpture. The increasing role of color in her sculptures had ramifications for Graves' prints-in¬progress: a new sensitivity to the structural as well as expressive potentials of color as well as a more decisive clarity of figure-ground relationship were distinctive achievements in such prints as Neferchidea (1979-85). The opportunity of working closely with the Rossis in New York enriched the collaborative dialogue and the ensuing prints, The Clash of Cultures and Borborygmi (1988), display even greater lucidity of design as well as a rich articulation of surface that are products of Graves' more manifest skill and confidence with her media.

In contrast to Graves' more gradual involvement with printmaking, Segal's immersion was total and unorthodox from the start. Known for his plaster sculptures of figures or groups in seemingly real environments, he was searching for a way of uniting two diverse artistic interests, namely, the making of sculptures from imprints of the human body and the making of vividly colored drawings. Segal credits Rossi with opening his eyes to the creative potential of prints for the enrichment of his art. During a visit to Rome, he suggested that the grease-coated bodies of workshop personnel be pressed against prepared soft-ground plates which led to the creation of the Blue Jeans Series (1974). The resulting imprints of skin, hair, clothing were uncanny as were the unprogrammed distortions resulting from bodily torsion and time. The etching process allowed Segal to retain some forms while editing or revising others. Crucial to the success of the prints was the acid color which enhanced the spatial tension between the figures and the dark aquatint ground. Despite Segal's enthusiasm for his new medium, further collaboration with the Rossi’s was delayed until the establishment of their New York workshop. There, in 1987, Segal produced the Six Portraits which are his largest prints to date and also figure among his most expressive and moving works in any medium. Shortly before making the prints, Segal had become interested once more in drawing, making numerous pastels but also producing one black and white drawing which Rossi saw in his studio. The artist was especially preoccupied with the way light hits objects and intrigued by the implications of the light and dark "messages" of old masters such as Rembrandt and Goya for his own work. Working for as long as nine or ten hours on a prepared aquatint plate, Segal once again used soft-ground etching to reinforce the aquatint blacks and to achieve tonal and textural effects. An amazing variety of marks - gashes, ghostly negative scratches on the aquatint, drypoint lines made with scrapers, brushes, nails, pieces of wood and even fingernails - enlivens the surface and adumbrates the tension that permeates these somber images. Repeated bitings of soft-ground also impart a physicality to the black areas and, at the same time, enhance the luminosity of the white paper. Apart from their remarkable achievement as commentaries on the means and ends of the graphic processes employed, Segal's recent prints have also served to clarify and inform the direction of his new sculptures.

While the creation of a complete printmaking facility in New York was a manifestation of the Rossis' desire to bridge the gap that separated them from a sizeable group of artists with whom they enjoyed a warm working relationship, it also signalled their recognition of the increasing "internationalization" of the city at the beginning of this decade. Interestingly, the Rossis' decision to expand their professional horizons coincided with the appearance in New York of a group of young Italian painters whose personal styles were subsumed under the label transavantguardia invented by the critic Achille Bonito Oliva. The organization of virtually simultaneous gallery shows and a prestigious exhibition at the Guggenheim Museum spotlighted such painters as Francesco Clemente and Enzo Cucchi whose subsequent rise to prominence was at once rapid and international. Clemente's first print, Semen (1987), was an immediate ban ii firer thanks to his capacity to assimilate technique. Rossi considers him one of those rare artists who can visualize the work in the plate. Combining thin, gaseous-colored aquatint washes with fluid etched line, Clemente attained a physical lightness to sustain his floating disembodied image. Working with Cucchi energizes Rossi who responds to his poetic sensibility and his spontaneity. Techniques are never programmed, but evolve with the image. Rossi maintains that "Cucchi is an artist who likes to exploit everything we do, everything we've done," and such prints as the giant triptych Lupa di Roma (1984) substantiate this statement. The complexity of techniques employed, rich contrasts of color and tone, and spectacular relief effects serve to recall and extend the innovative research that began with the prints of Fontana, Burri, and Turcato, reinforcing the impression of cohesiveness and continuity that is the mark of a great workshop's production.

As its first twenty-five years and more than eight hundred prints attest, 2RC Editions' contributions to the history of printmaking are indeed impressive. By creating conditions which liberate the artists from the constraints of technique, the Rossis have allowed them to explore their imagery with complete freedom, and, in the long run, this has engendered a more profound understanding on their part of the distinctive components of the medium. Surmounting material, logistical, and temporal obstacles with infectious enthusiasm and technical ingenuity the Rossis have helped make intaglio prints a vital and independent art form of truly international dimensions.